Saturday, November 24, 2007

One step deeper...

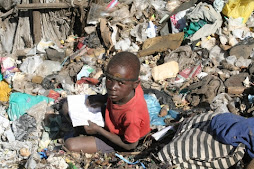

For the past two months, Mandy and I have seen, touched, heard, smelled, laughed, cried and even pooped the molecules of life in the slums of Nairobi. At times, we have found ourselves building an immunity to the beauty and affliction while other moments provoke the inevitable gulping contraction of the throat. There are many estimates out there on how many people live in the 170 slums of Nairobi, the most common exceeding 2,000,000. We have come to wonder where all of these people come from, the stories that frame their existence and the journeys that they have embarked on.

This week, I had an opportunity to join a group of people a group from Seattle through World Concern (a development non-profit out of Seattle who is doing some great work www.worldconcern.org) for a visit to Narok, a Maasai area in southwest Kenya. It was here that I was confronted with the realities of many of the people living in rural villages throughout Kenya, the adjustment that they must face when journeying to a city of 4 million and the beautiful people and place that they temporarily (or perhaps forever) abandon. Life outside of the most developed city in East Africa is different to say the least. My first day in Narok brought me back to September 7, when we landed at Nairobi's airport. With little confidence in language, a paralyzing mindset to be culturally sensitive while attempting to manage my senses and the life of the Maasai took its toll.

Perhaps the picture can best be painted through the story of a man named Peter.

Peter grew up in traditional Maasai culture. No electricity, no water, one father, many mothers, hundreds of cows and goats, no education, perplexity at the sight of a car and calloused feet from his miles explored each day. His mother was the first wife, feeling robbed of sharing her family and resources with others. Maa was the language of choice in and among his people while his land was similar to the most remote places of Nevada, New Mexico and Utah as his people were confined to barren areas by the colonizers. (sound familiar?) I hate to use the word primitive as it implies that society has advanced through industrialization and technology, (What has it advanced toward?) but it is the only word in my mind to adequately describe the live of rural villagers in Kenya.

Imagine life without plastic, with life possessions on one shelf and under the cow hide bed, being trapped in a carbon monoxide dungeon every day with a cooking fire inside of a windowless hut and never really seeing or needing access to money.

At the age of 12, Peter was told by his father to take over the foraging goats on a graze in quest of food and water. These journeys are ongoing, spanning across the region and often led solo or with a pair of Maasai boys. Days or perhaps weeks into his journey, he did what most 12 year olds would do, fell asleep and lost the herd of goats. Upon waking up, they were nowhere to be found. Even though he could see miles across the desert landscape, his goats were gone. He returned home to tell his father of his careless mistake. Needless to say, his father was incredibly upset.

Ironically, a few weeks later, the police came to the village and mentioned that there were a few openings in a boarding school near Nairobi. Convinced that his son was a shame to the tribe, Peter's father sent his son with the police with few reservations. This was the beginning of Peter's educational journey through primary school, secondary school and eventually university. Unfortunately, Peter's siblings were strong herdsman, warriors and sought-out girls and women bound for marriage and never had the opportunity to be punished by being sent to school.

I am not sure how the next steps panned out in Peter's life, but know that he is now back in his community, eventually accepted by his family and tribe and working with orphans and vulnerable children in rural areas. I was most intrigued by what the car ride must have been like for him as he entered into Nairobi for the first time, seeing multilevel buildings, at abundance of produce at stands lining the streets, traffic jams, brick walls around homes, watchman, restaurants and car alarms.

It is no wonder that many people end up in the slums. While I realize that this is not the path of a good chunk of the 2,000,000 people living in nearly inhumane conditions, at some point in time, families moved to the city in search for a better life. Life better than Kibera, Mathare, Kawangware and Lunga Lunga. Perhaps there is comfort in being surrounded by those who have experienced the same contrast, by those who have lost their goats and by those who were punished by a trip to the city.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment